Japan is home to over 1,000 regional traditional crafts. Some are even officially approved by the country. This article will introduce 9 different regional traditional crafts from the Chubu region: Ojiya-chijimi, Takaoka casting, Wajima-nuri lacquer ware, Mino washi paper, Kiso lacquer ware, Koshu crystal carving, Suruga bamboo ware and Tokoname-yaki ware.

Where is the Chubu region?

The Chubu region locates in central Japan, between the Kanto and Kansai regions. It consists of these nine prefectures: Aichi, Fukui, Gifu, Ishikawa, Nagano, Niigata, Shizuoka, Toyama and Yamanashi. In the Chubu region, you can find Mount Fuji, the tallest mountain in Japan.

About Japanese Traditional Crafts

Japanese traditional crafts are items that have been created and used in daily life throughout Japanese history. Some of them have a special approval from the Ministry of Economics, Trade and Industry.

Conditions for Approval by the Ministry of Economics, Trade and Industry

In order for a traditional craft to be officially approved by the Ministry of Economics, Trade and Industry, it must follow these requirements:

・ The item must be practical for everyday use

・ A significant part of the item must be hand-made

・ The item must have a history of at least 100 years, and must still be made using traditional techniques.

・ The item must be made with the same items that were used at least 100 years ago

・ The item must have a significant presence in its originating region and be created there.

As of 2018, there are 230 traditional crafts that have met these conditions. Tokyo is the prefecture is the most number of them, with 17 traditional crafts.

Check out this article to read about traditional crafts from the Chugoku region:

Japanese Traditional Crafts: Chugoku Region

1. Ojiya-chijimi (Niigata)

Ojiya-chijimi

Ojiya-chijimi is a hemp fabric from Niigata. It is characterized by the wavy design on the surface, called “chijire”. The fabric is mostly used in kimonos.

In 1955, Ojiya-chijimi was designated a national intangible cultural property. In 2009, it was designated as a UNESCO Intangible World Heritage Property.

Niigata prefecture is famous as a kimono producer, and has other famous fabrics such as the Echigo-jofu and the Tokamachi-gasuri. The Ojiya-chijimi, however, is considered the highest in quality and has been loved by feudal lords.

Ojiya-chijimi was created around 1670 by a man named Hori Masatoshi. He took some Echigo-jofu fabric and made some improvements to create Ojiya-chijimi. It became popular instantly, and at its peak, it sold over 200,000 pieces in a year.

Its popularity stems from its breathability and comfortableness. The fabric’s lumpy texture keeps it from becoming sticky with sweat, making it perfect for Japan’s humid summers.

Ojiya-chijimi is made entirely by hand. One important process is “yuki-sarashi”, where the fabric is laid out in the snow for it to naturally bleach. It is a famous process, and is a popular sight amongst tourists.

2. Takaoka Casting (Toyama)

Takaoka Casting (Photo credit: Takaoka City)

The city of Takaoka is Japan’s largest metal ware producer, and the home of Takaoka casting. Some products of Takaoka casting include vases, incense burners, Buddhist altar items, bells and more.

In 1611, the lord of the Kaga Domain, Maeda Toshinaga, brought 7 metal-casting craftsmen to Takaoka help the castle town flourish. Initially, the craftsmen made works of art to present to feudal lords. Later, they began to make items such as vases and Buddhist altar equipment, and those spread nationwide.

During the Meiji Period (1868 - 1912), Takaoka metal ware was displayed at worldwide events, such as the Paris exposition. Today, about 90% of the metal ware made in Japan is from Takaoka.

Kanaya-machi street

Kanaya-machi is where the metal casting factories were made for the 7 craftsmen. Today, the stone streets and the traditional houses still remain.

There are four different techniques used to create Takaoka metal ware: the rou-gata (wax-pattern) technique used mainly for artworks, the yaki-gata (dry mold) technique used mainly for sculptures and Buddha statues, the sou-gata (double mold) technique used mainly for pots and bowls, and the nama-gata (soil) technique used mainly for vases.

In particular, the nama-gata technique is commonly used in Takaoka metal casting. It allows craftsmen to make several works from one mold.

3. Wajima-nuri Lacquer Ware

Wajima-nuri bowl

Wajima-nuri lacquer ware is now one of Japan’s representative traditional craft items. It originated in the city of Wajima in Ishikawa prefecture’s Noto peninsula. This is the only lacquer ware craft designated as the country’s important intangible cultural property.

Lacquer ware are objects covered with lacquer, which comes from tree sap. There are over 20 steps in creating Wajima-nuri lacquer ware, with most of them done by hand. Wajima-nuri is special in that there can be up to 75-124 careful steps in creating the objects, and as a result, the colors of the lacquer ware can last for hundreds of years.

The oldest existing Wajima-nuri lacquer ware is from 1524. However, some theories suggest that it originated as long a 1,000 years ago from China.

The humid, rainy climate of Wajima allows for the thick lacquer to dry. This is one of the reasons why Wajima became a significant producer of Wajima-nuri lacquer ware.

Wajima-nuri every day items

Only items made with all natural material are considered true Wajima-nuri lacquer ware. Just because it was made in Wajima doesn’t make it a work of Wajima-nuri.

4. Echizen-yaki ware (Fukui)

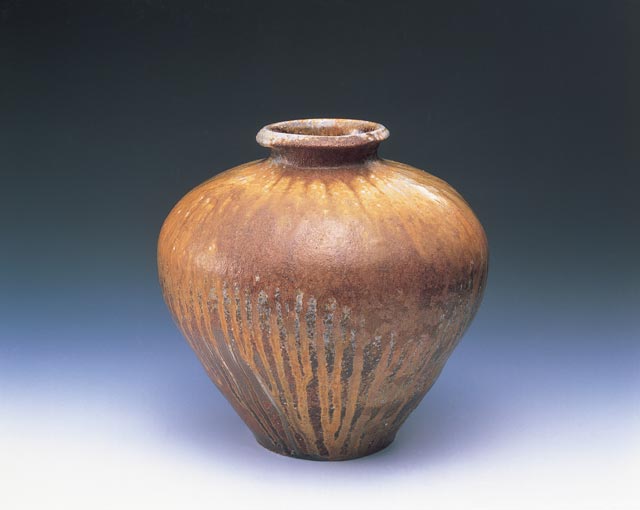

Vase (Photo credit: 福井県観光連盟)

Echizen-yaki ware is made in the town of Echizen in Fukui prefecture. It is one of Japan’s 6 major kilns, and was designated as a Japanese heritage in 2017.

The soil used for Echizen-yaki is high in iron, resulting in a reddish-color when finished. The finished wares are very leak-proof, and were often used to preserve water or sake.

Echizen-yaki dates back to the Heian Period (794 – 1185). Pottery techniques from Aichi prefecture were brought into Echizen during this time.

During the late Muromachi Period (1336 – 1573), Echizen-yaki works were shipped throughout Japan on the Kitamaebune ship. Echizen became the largest pottery workshop area in western Japan. Entering the Edo Period (1612 – 1867), they began to glaze the Echizen-yaki works. However, the glaze technique became unused in about 10 years.

Though the popularity of Echizen-yaki once declined in the Meiji Period (1868 – 1912), it began to regain attention after World War II.

Echizen-yaki (Photo credit: 福井県観光連盟)

Echizen-yaki wares are popular for their simple look and warm colors. The warm colors come from the iron properties in the clay. They are usually unglazed, but have a bit of shine due to the natural glazing that occurs in the kiln.

5. Mino washi paper (Gifu)

Mino washi paper

Mino washi paper, from Gifu prefecture, is one of Japan’s three major washi papers along with Echizen washi from Fukui and Tosa washi from Kochi.

When exactly Mino washi was created is unknown, but it is thought to have been around from at least 1,300 years ago. There are records showing Mino washi being used in documents from the Nara period (710 - 794).

The three ingredients used in washi making are mulberry, mitsumata and ganpi (all plants). These three ingredients plus cool, clean water is needed to make washi, and Mino is home to all of those conditions.

The main ingredient for Mino washi is mulberry. The mulberry found in Mino is known for its high quality. During the Muromachi period (1336 – 1573), people from all over the country would come to Mino to purchase its high-grade washi.

In the Edo period, Mino washi was often used for paper screens on sliding doors. By providing Mino washi for the government, Mino washi makers were exempt from paying some taxes.

Even within Mino washi, there is a special top-quality washi called Hon-minoshi. It is only made by a few, chosen craftsmen with the use of state of the art tools. In 1969, it was designated as a national intangible cultural property, and in 2014, it was designated as a a part of the UNESCO Intangible World Heritage, “Washi, craftsmanship of traditional Japanese hand-made paper”.

Mino washi lamp

The special straining technique used in making Mino washi allows it to have a smooth surface. Mino washi is used in items such as paper screens, letter sets, dresses, dolls and more.

6. Kiso lacquer ware (Nagano)

Kiso lacquer ware (Photo credit: Nagano Tourism Organization)

Kiso lacquer ware is made in the Shiojiri area of Nagano prefecture. There are many painting techniques used to create Kiso lacquer ware, such as the Tsuishu technique, Roiro technique and the Makie technique.

Kiso lacquer ware originated around 400 years ago, in the Shiojiri area, with support from the Owari Tokugawa family (related to the ruling Tokugawa clan). During the time, Kiso lacquer ware was a popular souvenir for those traveling on the Nakasendo route, which connected Edo (Tokyo) and Kyoto.

The Shiojiri area has a high temperature difference year-round, making it an ideal environment for trees such as hinoki and katsura to grow. Hinoki and katsura are the main material used to create Kiso lacquer ware.

During the Meiji period, a type of soil containing a large amount of iron was found. This allowed for lacquer ware creations to be sturdier, and more Kiso lacquer ware works were created.

Kiso lacquer ware bowl (Photo credit: Nagano Tourism Organization)

Kiso lacquer ware has been used to create items for day-to-day life, but in recent years, luxury Kiso lacquer ware items have been created as well. One in particular is the “menpa”, a traditional lunch box.

7. Koshu crystal carving (Yamanashi)

Koshu crystal carving is a traditional craft from Yamanashi prefecture. The intricate, detailed designs on the crystal goods are all hand-carved. Each of the crystals used are natural and one of a kind.

The craft began when crystals were found at Shosenkyo Gorge around 1,000 years ago. For a long time, the crystals were left untouched and used as sculptures. In the latter half of the Edo period, a carving craftsman was invited to Yamanashi from Kyoto, and invented some crystal carving techniques.

There are seven steps in total in Koshu crystal carving, from picking the right crystal to giving it its final touches.

Crystal picking is no longer done at Shosenkyo Gorge. Instead, many different types of crystals are imported, and craftsmen spend their time choosing the right ones to carve.

Crystal carving is difficult even for experienced craftsmen, since each crystal has its own unique shape to it. Koshu carved crystals are used for sculptures, accessories and more.

8. Suruga bamboo ware (Shizuoka)

Suruga bamboo ware, from Shizuoka prefecture, is a traditional craft approved by the Ministry of Economics, Trade and Industry.

The strands of bamboo used in Suruga bamboo ware, called “takesensuji”, are thinly cut specially for this craft. The diameter of these strands measure around 0.8 millimeters.

The Suruga region has been a prominent bamboo producer throughout history. Bamboo artifacts from the Yayoi period (300BC – 300) using Suruga bamboo have been uncovered in tombs.

Since the early Edo period, the Suruga province was known as a place where many craftsmen gathered. In 1840, men from the Okazaki Domain (current day Aichi) brought over bamboo craft technology into Suruga, and that is when the Suruga bamboo ware craft began.

The four steps in creating “takesensuji” Suruga bamboo ware, called higo-tsukuri, wa-zukuri, ami and kumitate, are all done by one craftsman. The curvature of the bamboo strands and its natural colors are some of its characteristics.

9. Tokoname-yaki ware (Aichi)

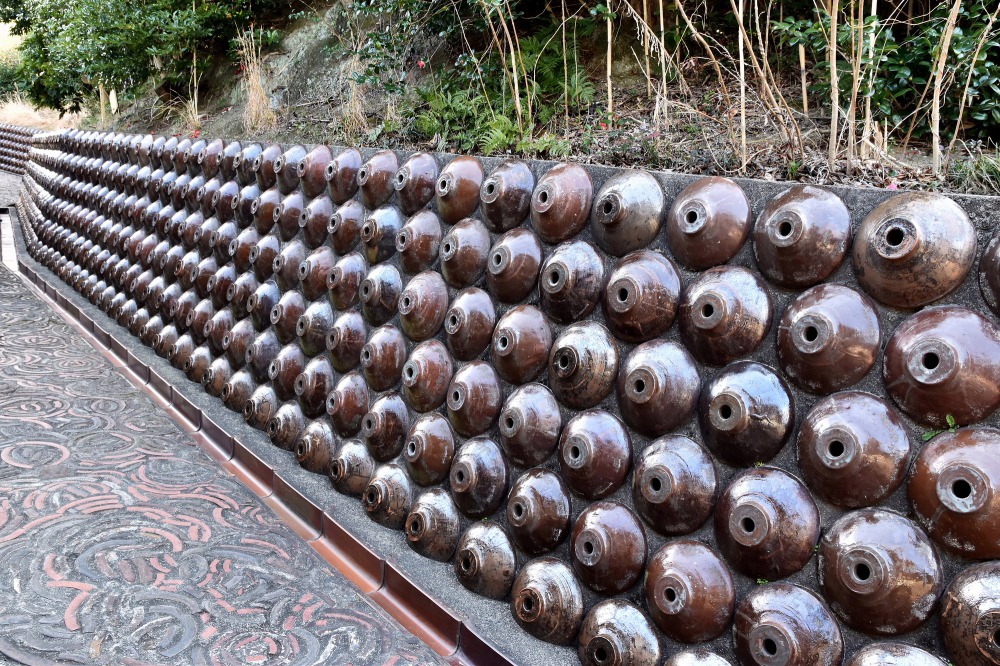

Tokoname-yaki ware on the side of a road

Tokoname-yaki, from Aichi prefecture, is also one of Japan’s six major kilns. It uses clay rich in iron, resulting in it having a coppery, reddish color. Its location on the coast of the Ise Bay allowed Tokoname-yaki to be the biggest producer out of the six major kilns.

The history of Tokoname-yaki dates back to the Heian period. About 3,000 kilns were created throughout the Chita Peninsula in southwestern Aichi.

Initially, Tokoname-yaki creations were mostly items such as bowls and vases. However, entering the Kamakura period (1185 – 1333), items as tall as 50 centimeters were made. Most items in the Muromachi Period were large items.

Entering the Meiji period, production increased with the help of western technology. The variation of types of items produced increased as well. In 2017, Tokoname-yaki ware was designated as a national heritage.

Tokoname-yaki teapot

Teapots are one of the representative Tokoname-yaki items. The iron oxide in the Tokoname-yaki teapot is said to react with the compound tannin (found in tea), and makes the tea more flavorful.

DIY Japanese Traditional Crafts

In most regions throughout Japan, you can find gift shops selling the region’s representative traditional crafts. If you want a more hands-on experience, you can look for traditional craft-making experience courses.

_600x400.jpg)

_600x400.jpg)