In Japan, there are over 1,000 regional traditional crafts, with many of them even being officially approved by the country. This article will introduce 7 traditional crafts from the Kanto region of central Japan: Kasama-yaki ware, Karasuyama washi paper, Takasaki daruma doll, Boso uchiwa fan, Ogawa washi paper, Edo-kiriko cut glass and the Hakone yosegi box.

Where is the Kanto Region?

The Kanto region is made up of Chiba, Gunma, Ibaraki, Kanagawa, Saitama, Tochigi and Tokyo prefectures. It is on the central-eastern coast of Honshu, Japan’s main island. About 1/3 of Japan’s entire population lives in the Kanto area, as it is where major cities like Tokyo and Yokohama are located.

About Japanese Traditional Crafts

Japanese Traditional Crafts are items that have been created and used in daily life throughout Japanese history. Some of them have a special approval from the Ministry of Economics, Trade and Industry.

Conditions for Approval by the Ministry of Economics, Trade and Industry

In order for a traditional craft to be officially approved by the Ministry of Economics, Trade and Industry, it must follow these requirements:

・ The item must be practical for everyday use

・ A significant part of the item must be hand-made

・ The item must have a history of at least 100 years, and must still be made using traditional techniques.

・ The item must be made with the same items that were used at least 100 years ago

・ The item must have a significant presence in its originating region and be created there.

As of 2018, there are 230 traditional crafts that have met these conditions. Tokyo is the prefecture is the most number of them, with 17 traditional crafts.

Check out this article to read about traditional crafts from the Tohoku region:

Japanese Traditional Crafts: Tohoku Region

1. Kasama-yaki ware (Ibaraki)

Kasama-yaki

Kasama-yaki originates from the city of Kasama in central Ibaraki. This method of pottery was invented in the 18th century, when Kuno Hanzaemon, a man from Hakoda village (present-day Kasama) was taught pottery by a potter named Chozaemon from Shiga prefecture.

The pottery style flourished in the Kasama Domain, and by the Meiji period (1868 – 1912), there were 19 Kasama-yaki studios. Although the popularity of it took a downward turn due to the spread of plastic ware, Kasama-yaki regained recognition after Ibaraki set up a prefectural pottery workshop in 1950.

Process of making Kasama-yaki

There are eleven total steps in making Kasama-yaki ware. It begins with digging up the clay, and ends with smoothing out the surfaces of the final product. Each step requires the careful skill of a Kasama-yaki professional.

It is said that the characteristics of Kasama-yaki is that there are no characteristics at all. By that, it means one is allowed to do basically anything they want to do with their Kasama-yaki work. There are no traditions or rules to stick to, and each potter is allowed to express whatever they desire through their work. In recent years, Kasama-yaki is used to create interior art works and objects.

2. Karasuyama washi paper (Tochigi)

Karasuyama washi paper comes from the city of Karasuyama in Tochigi prefecture. It has a history of around 1,200 years, and is designated as a national intangible cultural property.

In around 610, paper made its way into Japan from China. Later, Japan made its own form of paper, called washi, with tree bark. It is unclear when exactly washi making began in Karasuyama, but it is said to be some time around the Nara period (710 - 794), since it has been mentioned in writings of those times.

Entering the Kamakura period, Karasuyama washi began to be used in important documents used for imperial purposes.

There were four types of Karasuyama washi during that period: Hodomura-gami, Dan-shi, Jumonji-gami and Nishinouchi-gami. Hodomura-gami was the thickest and sturdiest of them all, and was the most valuable. To this day, it is the representative form of Karasuyama washi.

The main ingredient of Karasuyama washi is the Nasu mulberry tree. The Nasu mulberry is said to be the highest quality mulberry in Japan, and is the reason why Karasuyama washi can be made into such high quality.

The bark from the Nasu mulberry is first boiled to remove any impurities. After it is dried, then the Karasuyama washi is complete. Karasuyama washi is made into paper items such as postcards, letter sets and even dolls and wallets.

3. Takasaki daruma doll (Gunma)

Takasaki daruma doll

Takasaki daruma dolls are created in the Takasaki city area of Gunma prefecture. With lucky animals such as cranes and turtles drawn onto the face of the dolls, the Takasaki daruma is known as the “lucky daruma”.

Daruma dolls are round, red dolls that are used as a good luck talisman in Japan. It is also used as a talisman in goal setting. Although they are already originally considered good luck, the Takasaki daruma is seen as extra lucky.

Production of the Takasaki daruma began about 200 years ago during the Edo period. A man named Yamagata Tomogoro began making these dolls. They were only made in the Yamagata household, as the red paint was not easily available throughout the prefecture.

In 1859, when Japan began opening their doors to foreign trade, they were able to get more red paint from overseas. Currently, about 80% of daruma dolls are made in Takasaki.

Before being painted red…

The dolls are made in the order of creating the base, painting and finally drawing on the face. Although there is a traditional way of hand making the shape of the dolls, this step is now mostly done by machinery as it takes up less time. Painting the dolls red is also often done by machinery, but drawing on the face is always done by hand.

The Takasaki daruma doll has good luck symbols all over it. Other than the lucky animals drawn on the face, it also has the word “福入”, meaning “enter luck”, on its stomach, and word such as “家内安全” (household safety) and 商売繁盛 (business prosperity) written on its shoulders.

You can choose from various sizes of the daruma to buy. Buy a small one to bring to friends and family as a good luck charm!

4. Ogawa washi paper (Saitama)

Ogawa, a town in Saitama prefecture, is known as a place of creative manufacturing. Ogawa washi paper, in particular, has a long history, and has been a significant part of the townspeople’s’ lives.

Dried mulberry bark

Washi making in Ogawa began about 1,300 years ago. The town had always been abundant in nature, and had plenty of mulberry for washi production.

Entering the Edo period (1603 – 1868), Ogawa washi began to spread nation wide. Washi had originally been used only amongst the wealthy, but since Ogawa was conveniently located near Edo (present day Tokyo), many manufacturers were able to gather there and mass-produce high-quality washi. As a result, washi was made available for people of all social classes.

To this day, Ogawa washi is made and used throughout Japan. It was registered as a part of the UNESCO intangible cultural heritage series of “Washi, craftsmanship of traditional Japanese hand-made paper”.

Ogawa washi is still mostly entirely hand-made. Craftsmen pass down their skills generation by generation and keep the tradition alive. Today, you can find Ogawa washi in the form of notes, business cards, post cards, fans and more.

5. Boshu uchiwa fan (Chiba)

Boshu uchiwa (Photo credit: ©南房総市)

The Boshu uchiwa fan has a history of over 100 years, and originates from Minami-Boso region of Chiba prefecture. Along with Kyo-uchiwa from Kyoto and Marugame uchiwa from Kagawa, Boshu uchiwa is considered one of the three major uchiwa fans of Japan.

Uchiwa-making began in Boso because of the great weather in the area. The main ingredient of uchiwa fans is the Simon bamboo, which grows in warm areas. This kind of bamboo is found abundantly in the Boso peninsula.

Boso uchiwa production began in the Meiji Period (1868 – 1912), when Iwaki Sogoro, a bamboo seller, invited over craftsmen from Tokyo to create uchiwa.

In 1923, after the Great Kanto Earthquake, many uchiwa craftsmen in Tokyo moved to the Boso peninsula. Since then, uchiwa production in the area had increased significantly.

A particular characteristic of the Boshu uchiwa is the very round edges and the light, intricate bone structure that is made of 48 to 64 parts. The fan is completed in a total of 21 steps, and the result is a simple yet sophisticated design.

6. Edo-kiriko cut glass (Tokyo)

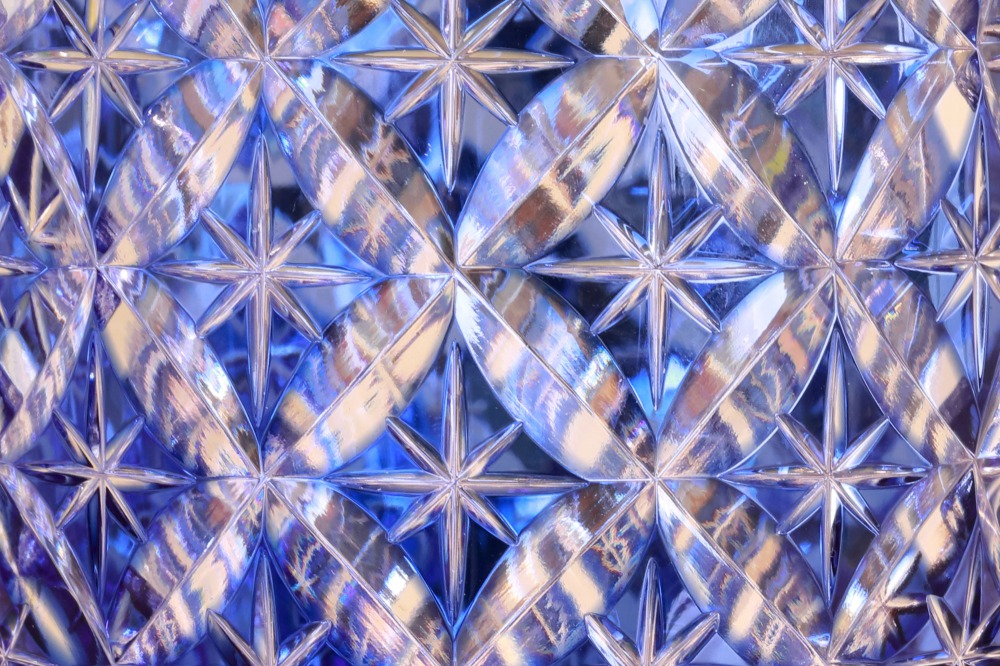

Edo-kiriko glassware

Edo-kiriko is a cut glass work founded in Tokyo. It began in 1834, when Kagaya Kyubei, an owner of a glassware store, began making his own cut glass after being inspired by those from Great Britain.

Entering the Meiji Period, a glass factory was made as a part of the government’s initiatives for Japan to westernize. More western details were added to Edo-kiriko, as British cut glass craftsman Emmanuel Hauptmann visited to spread his glass-cutting skills.

There are four major steps in Edo-kiriko making. First is called “wari-dashi/sumi-zuke”, where the outline of the patterns is pressed onto the glass. Then during the next step, called “arazuri”, the glass is put on a spinning table, and crevices are made into it. Next, after the designs are created, the “ishigake” process is done, where the glass is smoothened out. Finally, in the “migaki” process, the glass is polished to a shiny finish.

Creating the designs is very difficult, and even a skilled craftsman can only make a few Edo-kiriko works a day.

Intricate designs on Edo-kiriko glass

The designs on Edo-kiriko glass are inspired by plants such as chrysanthemums. There are many traditional patterns, such as the “nanako”, inspired by fish eggs, and “kiku-tsunagi”, inspired by chrysanthemums.

7. Hakone yosegi box

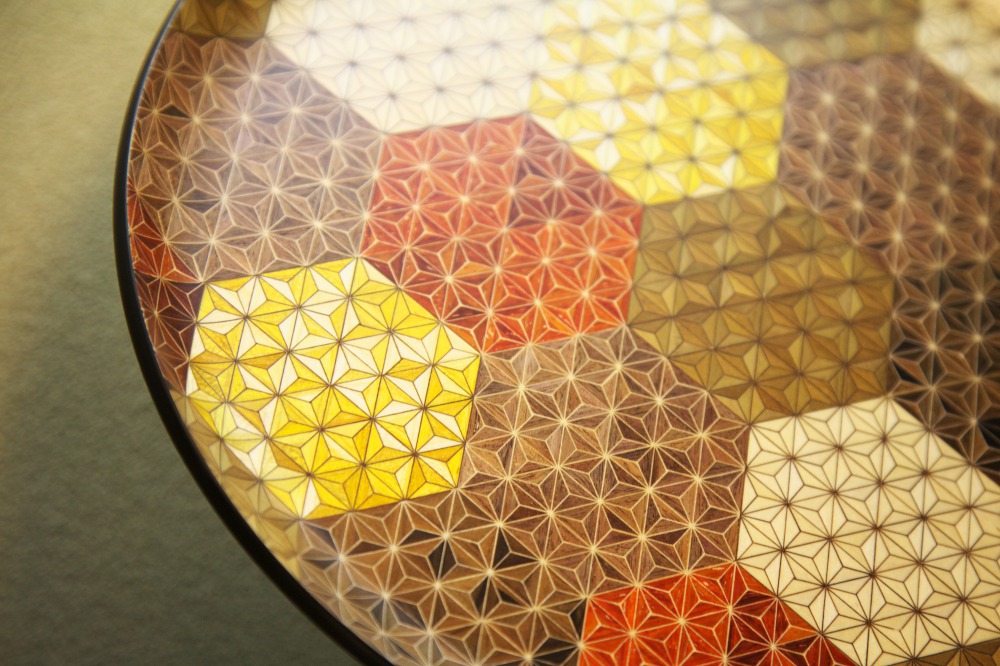

Hakone yosegi plate

From Hakone, a popular onsen town in Kanagawa, we have the Hakone yosegi box. The boxes are made from several different types of wood.

The Hakone yosegi technique originated in the late Edo Period. The Hakone area is surrounded by forests of many different types of trees, making the Hakone yosegi technique possible. Ishikawa Jinbei, a man from the Hakone area, brought back the woodwork techniques from nearby Shizuoka prefecture and did it with the timber found in Hakone.

In 1853, after Commodore Perry came to Japan to open up the country’s ports for trade, Hakone yosegi items began to popularize as a Japanese souvenir. This helped Kangawa’s economy flourish, and today, Hakone is one of the few places in Japan that still follow the traditional yosegi woodwork technique.

Geometric patterns

One significant characteristic of Hakone yosegi is the geometric patterns. These patterns are created by layering several different pieces of wood and cutting them. The individual pieces of the patterns are pasted onto a wooden board to create boxes.

Nowadays, items such as Hakone yosegi cups, kitchenware, mouse pads, rulers and more can be found.

DIY Japanese Traditional Crafts

In most regions throughout Japan, you can find gift shops selling the region’s representative traditional crafts. If you want a more hands-on experience, you can look for traditional craft-making experience courses.

_600x400.jpg)

_600x400.jpg)